The New Complexity

What will the world of engine development look like tomorrow? Answers will be provided at the Berlin Powertrain Symposium at the end of November

What will the vehicle drive system of the future look like? There is no straightforward, universal answer. For the developers, it is a case of finding the suitable approach against the backdrop of the various demands and technical options. In- tensified dialog with policymakers and within the industry might help to lead the way.

“The best thing to make of exhaust gas is power.” Hidden behind this snappy slogan is a pioneering achievement on the part of the engine developers at BMW. Presenting the 2002 turbo in 1973, they launched the first volumemanufactured sedan with exhaust gas turbocharging. 170 h.p. deliver a top speed of 211 km/h. At the time, this put the model among the kings of the fast lane. But the 2002 turbo was never a big seller. It came out at the time of the first major oil crisis which in Germany led to Sunday driving bans and gasoline prices the likes of which had never been seen.

Less is more

For powertrain developers, getting the timing right is crucial, back then just as it is today. Unlike the 1970s, though, one thing is now clear: the automobile trump-card logic of “higher, further, faster” is now definitely a thing of the past. Replacing the motto is “less is more”: fewer climate-damaging CO2 emissions, fewer exhaust pollutants. It is now about meeting challenging limit values without reducing the car’s utility value or even driving pleasure. For the engineers, this means: more technology, more complexity, more work.

The search for tomorrow’s drive system starts with statutory CO2 regulations. Europe still sets the standards the automotive world follows, more or less quickly. To date the goal has been to reach an emission level of no more than 95 grams of CO2 per kilometer in 2020. Here, the level a manufacturer needs to reach is determined by the average weight of all the vehicles it sells. But experts are expecting that it will also be necessary for premium manufacturers producing a particularly high number of large and heavy cars to arrive at a target level of less than 105 grams of CO2 per kilometer. For a combustion engine, this equates to a fuel consumption of 4.5 liters of gasoline or 4.0 liters of diesel over 100 kilometers. But that is not the end of the story.

According to VDA (German Association of the Automotive Industry) President Matthias Wissmann, the EU Commission will table a new proposal as early as the end of 2017. “The new fleet ceiling is to apply from 2030, possibly with an intermediate stage from 2025.” The direction is dictated by the German government’s climate protection plan. This states that greenhouse gas emissions from the entire transport sector are to be reduced by 40 percent by the end of the next decade. As a result, most experts are expecting a fleet limit value of between 68 and 75 grams of CO2 per kilometer.

As if the targets were not challenging enough, consumer purchasing behavior is pointing in the opposite direction. In 2016, no less than one in every five newly registered cars in Germany was an SUV or off-road vehicle. At 25 percent, the SUV segment grew more than any other. And complying with ever tighter exhaust emission regulations is making it harder for engine developers to concentrate on reducing CO2 alone.

In Europe, so-called “Real-Driving Emission” Tests (RDE for short) will be successively introduced from fall 2017 onwards. Exhaust pollutants – initially nitrogen, particulate emissions and carbon monoxide – will be recorded with mobile measuring equipment while driving on public roads. From 2020 and following a transitional period, new vehicles will only be allowed to emit the same amount of pollutants in real-world driving as on the test bench – plus a factor for measurement inaccuracy.

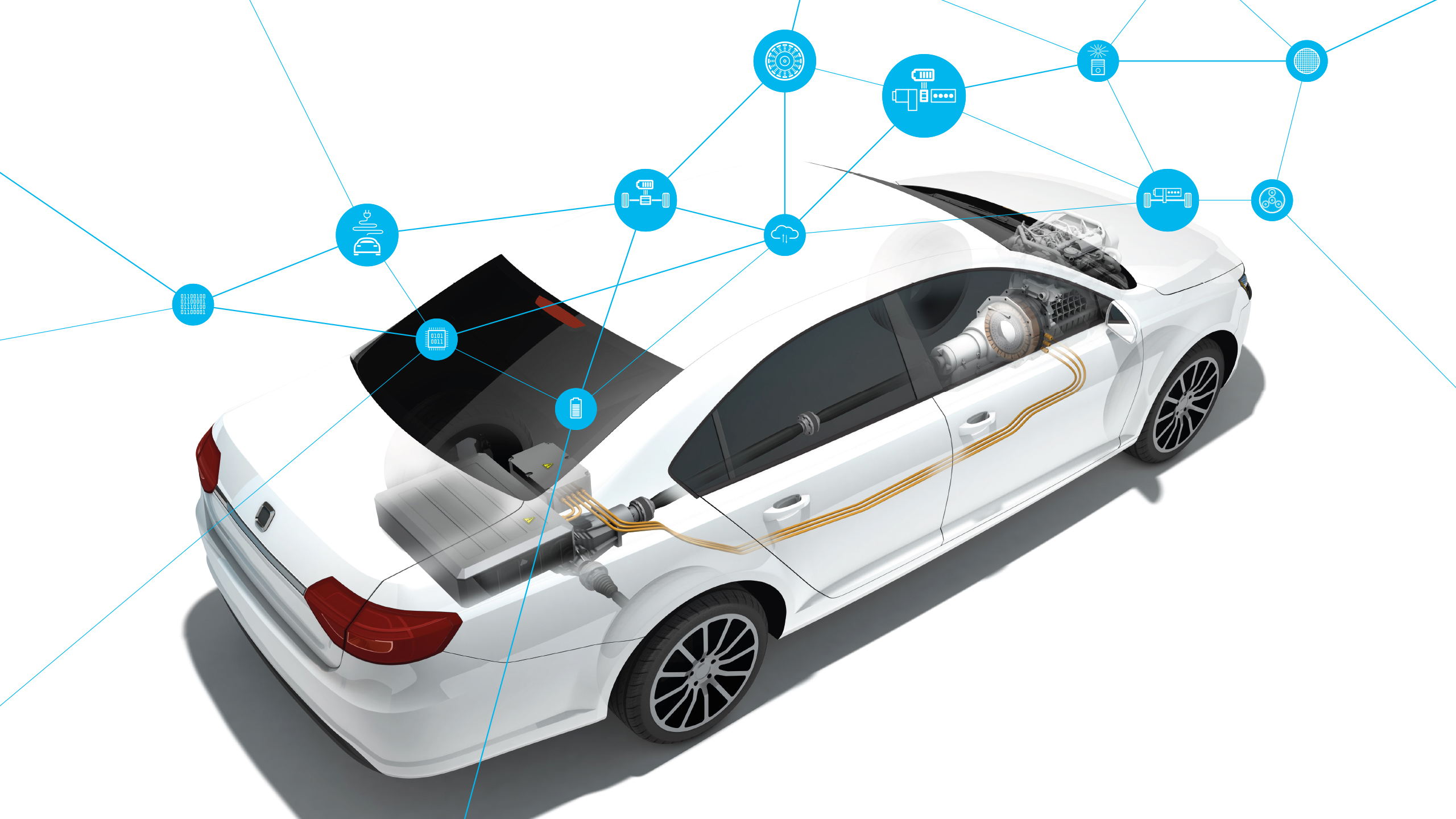

The crux of the matter: some of the technologies introduced as a result of the RDE regulation could end up increasing consumption. Despite all of the challenges, the engineers are not powerless. They have a whole arsenal of technology to reduce CO2 emissions and exhaust pollutants. Combustion engines and transmissions can be advanced, such as by varying compression, injecting water in highload ranges or a predictive shift point layout that knows the topography and traffic situation on the road ahead. The combustion engine can also cooperate with an electric drive. In its mildest form, this is a 48-volt system which, above all, makes it possible to recuperate most of the energy lost while braking. One option for large vehicles is a plug-in hybrid system in high-voltage technology that provides a range of up to 50 kilometers in all-electric mode.

And finally, there is still the battery electric drive all car manufacturers are now working flat out on. As emissions produced while the electricity is being generated are not attributed to the electric vehicle, they always show a flawless zero-gram balance. The extent to which this affects the fleet value will be determined solely by whether they can be sold in appreciable numbers.

Platform for dialog

The variety of technical solutions is immense, so too are the demands – particularly because every new drive system developed from scratch must prove itself on the world market. An equation system involving so many variables is not easy to solve even for engineers with good computing skills. “We will only be successful if we look at a manufacturer’s entire vehicle fleet and include all model ranges and markets”, says Matthias Kratzsch, Executive Vice President for Powertrain Systems Development at IAV.

In his division, a sophisticated methodology has been developed that in each case proposes the appropriate option from the millions of potential combinations. All the same, says Kratzsch, narrowing down the playing field, machine intelligence is only part of the solution. In this day and age, the boundary conditions software works with can change at lighting speed. This is why Kratzsch attaches importance to dialog with policymakers and other engineers. Organized by IAV, the Berlin Powertrain Symposium provides a platform for precisely this. “Even if we arrive at different answers”, Kratzsch says, “we all face the same questions.”